RH: I've fallen into the habit of starting by asking people how they got involved with Whole Earth so I'll do that with you as well.

AK: It started when I was a journalism student at Berkeley. I had created a small press magazine when I was an undergraduate at SUNY Albany. I went to small press conventions and all this stuff in the early 70s. I became a journalism student because when I graduated from college I wanted to be a writer. I hitchhiked to San Francisco and lived in a shared rental in the inner Richmond and tried to write. And I discovered that what I was writing was pretty bad. I came to the conclusion that it was because I didn't know anything about people and I was just gazing at my own navel. I was really down and out before I got into Berkeley. But there I studied graphic design, magazine publishing and journalism. I was the only person at the journalism school who did that. And I also took a class in computers because I had gotten involved in computer typesetting, which was nascent then. I put myself through Berkeley doing Compugraphic typesetting.

I had been very influenced by The Medium is the Massage and a lot of ideas by Marshall McLuhan. I knew very little about graphic design but I knew enough to put a magazine together. And I got very interested in the history of magazines. I discovered the extent to which advertizing shaped magazines - not just the text, but the look and feel and form. I thought that was really interesting and I wrote a prospectus for creating my own magazine. It was called "I'm interested in creating a magazine" and it included a brief history of magazines. Since I was a typesetter, I went to an offset printer and published it myself. I had found only two magazines published without advertizing that were really interesting: one was Mad Magazine and the other was CoEvolution Quarterly. They demonstrated what was possible if you had a commercially successful magazine without ads. So I wrote to Stewart and sent him a copy of the prospectus and said I'm interested in adapting the history part of it if you're interested in publishing it in CoEvolution Quarterly, because I think CoEvolution Quarterly is an amazing magazine and I've been studying magazines. I had no idea what the Whole Earth Catalog was at that time. Anne Herbert wrote back and said we really liked your history thing, Stewart and I, and as it happens we're doing a special issue on magazines and we want to use your history. By complete coincidence, they had sent out questionnaires to people around the world asking what magazines they read and the answers were coming back. I think you were one of them.

RH: That's right. I was one of them.

AK: So my piece ran next to the answers. It was very contentious because I came into the office and did my own graphic design and my own layout. The production staff could tell I was a total novice, but I used white space. And I was allowed to use white space! Stewart had never let anybody use white space in a layout. In fact he had been published somewhere saying white space is a waste of paper, if you need to rest your eyes look at a wall or something. And so here I was, sitting in the office, doing my own paste-up, a complete stranger. And Whole Earth was never kind to strangers.

Then Stewart wrote and offered me the chance to be research editor of the Next Whole Earth Catalog. This was in 1980 and I was about 26. By that time I had figured out what the Whole Earth Catalog was, but I didn't know the whole history. The ambience of CoEvolution Quarterly was like a small magazine that published really interesting things by interesting people. The fact that it came from the Whole Earth Catalog was sort of a sideshow to me. It was the past. I don't know who raised the idea of doing a Catalog again. It might have been John Brockman, it might have been Stewart. But the Next Whole Earth Catalog - and I'll take credit for coming up with the name, in a conversation with Stewart along the lines of: "what are we going to call this? We can't call it the Last Whole Earth Catalog, so how about the Next?" It was a very obvious thing to suggest.

Anne was the Catalog's managing editor. Among other things she coordinated traffic flow. She and Kathleen organized the system of buckets and paper. I was very much a neophyte thrust into the middle of it. We only had 9 months to do it. I came in January and it was due at the publishers in September, and we were starting at square zero. We had no material. So Stewart organised the finding of people to write, I organised the outreach to publishers to get books to review, and Ben Campbell, who already worked there, managed the flow of books. Everybody basically doubled the amount of hours that they were working. At the time I was living in San Francisco. I would bicycle one way over the Golden Gate Bridge to work, I would sleep in the office and bicycle back the next day to sleep at home. We later described our production system to a group called the Graphics Gathering in Silicon Valley. Howard Permutter, who organised that group and who I recently was in touch with, said that we pushed paper technology to its limits. In the same way that the Catalog anticipated the Internet, we kind of anticipated new ways of workflow with our production approach.

RH: It sounds like a baptism of fire.

AK: And I've been dealing with similar heroic efforts ever since. Throughout my career I have participated in projects that were just impossible but that managed to get done. So we finished the Catalog, then almost immediately began a second edition. I oversaw the research on that, too. At that point, Stewart realised that he had people who could take the reins of an issue and edit the magazine. Anne, if I remember correctly, didn't want to take that role. But I did. Stewart set it up so I alternated with Stephanie Mills as editor, and then with others like Jay Kinney. Then in 1983 we got another offer, to do a Whole Earth Software Catalog.

RH: Was this after the Whole Earth Software Review had started?

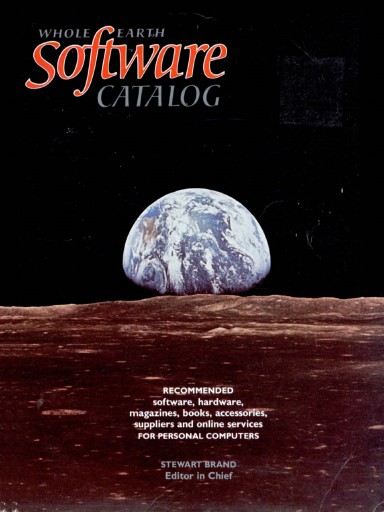

AK: No. Let me tell you the story. I want to be charitable but it's probably the worst business decision I ever saw Stewart make. It's one of the worst business decisions I ever saw anybody make. Stewart got a million dollars, maybe more, to do the Whole Earth Software Catalog. Brilliant idea, but we didn't have a magazine to draw on. When we did the Next Whole Earth Catalog, we had 7 years of CoEvolution Quarterly to start with, and alot of the great stuff in the Catalog was adapted from what we had already published in the magazine. But we didn't have that for software. And even if we had, everything would have been out of date. So how are we going to gather the information? We decided to publish the Whole Earth Software Review and for that we hired new people. I've written about this in my own book, Who Really Matters, which in Europe is called The Core Group. In order to get knowledgeable people to work on the Software Catalog we had to pay more than we normally paid. Until then everybody at Whole Earth made 10 dollars an hour. Even Stewart made a very small amount of money. Of course we could use the office to do outside work and many of us made alot of our income freelancing for other people while working at Whole Earth. But the people who came out of the computer industry simply were not going to work for ten dollars an hour. I helped organise the Software Catalog project and I insisted on thirty thousand a year, which was an incredible amount of money at that time. It allowed me to get my own apartment. And others on the software side were being paid similar amounts. But we didn't raise the pay for the established group at Whole Earth. So for the first time we had a bifurcated system and I was trying to make it work and keep everybody happy. It was a difficult position to be in.

RH: The new people were working on the Software Review?

AK: They were working on the Software Review but we also had the book. The Software Catalog had offices set up right across Gate Five Road. The book was really good, and everyone could see that. Everybody could see it was the wave of the future and it looked like we were going to be riding this thing really far. But two things happened. The first thing was that the Software Review was a full color magazine without ads. We'd always published magazines without ads, but this one was full color. Stewart thought, and we all agreed, that it would be really cool to publish a magazine that was immersive, but we also made it small, the size of Readers Digest. I still have copies of it. I wonder if other people have copies of it.

RH: I have issue number three, but that's all.

AK: That was the best one. Richard Dalton edited the first two and I edited the third. It was the first time I was really able to show what I could do as a magazine editor. Three issues were printed but then Paul Hawken had to break it to us that we wouldn't have money to publish any more. This was mid-summer 1984. We had just enough money to get the Software Catalog out. And we thought, great, the Software Catalog will bring us back into the black. But unfortunately, the Software Catalog did not. I don't know if the Software Catalog ever cleared the advance. Probably it didn't. So unlike the Whole Earth Catalogs, we did not get royalties from the Software Catalog. We didn't get that much from the Next Whole Earth Catalog either, because we had spent so much up front. The Software Catalog didn't do as well as we had hoped but we didn't want to stop writing about computers. The field was really exciting and we were good at covering it, so we came up with the idea of folding the Software Review into CoEvolution Quarterly and the combination was called the Whole Earth Review.

Whole Earth Software Review =

Whole Earth Review (January 1985)

RH: Art, I'm more naive than you are in this but what prevented you from continuing to publish the Software Review? Was it the gap between the cost of production and the income?

AK: The Whole Earth Software Review, the magazine, never began to earn enough money to cover its costs. It was a four-color magazine with no ads. It was also, in retrospect, the opposite of what readers wanted. I'm realising this for the first time as I'm talking. I think we were blinded by the fact that we had grown up in print. It may have been counterculture print, but it was still print and we loved the beauty of the page - compared to the still very clunky look and feel of most computer screens. The first desktop publishing device was at least a year away in the future. The Macintosh had just come out and computer graphics were not photographic. So at this stage, if you were aware of how earthshaking software was, the only way to express it - we thought - was through the medium of print. But people who were involved in software and computers couldn't care less. They were already living in their future.

RH: Are you saying that the color and design of the magazine were total wastes?

AK: Let me phrase it differently. Software architecture was a more compelling environment, even though it was graphically rudimentary, than the state-of-the-art, glossy, high-touch graphics of our jewel-like Whole Earth Software Review. And we missed it. Whether we missed it or not, we liked what we were doing and we were completely on the wrong side of history. So we created what was probably the most precious computer magazine ever produced. It was brilliant but it failed to find an audience. We had some really classic writers on various programs, various topics and themes. We had a software geneology that brought in experts on the history of computers. We had Steven Levy on games. We had Mark O'Brien on software for the disabled. We had great James Donnelly cartoons. We had amazing people writing and beautiful artwork.

RH: Why do you think it failed then? You can't say it failed because it was too good.

AK: There was no market for a Vogue for computers - not that we were Vogue, but we were probably as close as one could be. There was a market for what works, what's fast and efficient. There was a market for logic, and logic was just as good on newsprint. What we produced was the opposite of a quick, dirty, get-it-out-the-door prototype, and we suffered as a result. Nobody cared that it wasn't paid for by advertising. The irony is that if we had made it like the original Whole Earth Catalog, back when it was a quarterly newsprint publication, Stewart would now be one of the wealthiest people in the world.

RH: But you could see it wasn't selling. That must have led to recriminations.

AK: No. I did not see what I just described to you until years later. And I would never fault Stewart for choosing to print in color. I was just not paying attention to the sales because I was immersed in "if you love it they will come," "do what you love and the money will follow." We did what I loved and the money did not follow! But I can't complain. I certainly learned alot about business. I had not been involved in business decisions before and I ultimately became Whole Earth's business writer - largely because there was no one else doing it. Michael Phillips was not really interested in continuing as the maven Whole Earth needed on this subject, and there wasn't anyone writing about what big business is doing or how to get a job or any of that stuff, so I took it on. That was in the latter half of the 1980s. By that time, I was gone, moved back to New York. I had left Whole Earth in 1985. I was burned out by writing about computers. I was especially burned out because I was covering telecommunications. You were the other person covering telecommunications but what you knew was radio and broadcast. I was the only other person who really had a handle on this new medium and how it was changing behavior. The most important aspect of that, as we all later learned, was connecting and enabling people. In theory, great. But when it actually came to the coverage Whole Earth needed, it meant I was testing modems and telecom software. I was a users consultant on EIES, and running the Whole Earth Forum on Compuserve but I wasn't doing any of it particularly well. I really buy Sturgeon's Law - "90% of everything is crap" - though I desperately want to be producing stuff that is not crap most of the time. And I tend to work with people who feel the same way. But after the Software Review ended, 98% of what I was doing was crap, so I was really depressed. I was in screaming rages at busted machines. I was unable to control my equanimity. So I decided to move back to New York. I came back in January 1985. Faith and I got involved - we met at a small press magazine meeting that year and we're still married. She did not want to leave New York, so I decided to move back to New York permanently.

I went back to California to do several more pieces for the San Francisco Bay Guardian, where I was also a reporter. And when they did the Essential Whole Earth Catalog I did the business section and a couple other things. When they did the Millenium Whole Earth Catalog I think they drew me in to do the business section again. But I knew very little about business, and arguably, I still know very little about business. But I know alot about business books and I know a fair amount about consulting. For a while I fell into the trap of being a computer writer, which was awful because I was writing about really boring things. This was around the time the Global Business Network was being started and I ended up doing some reports for them. And I met Harriet Rubin, a book editor at Doubleday who had started her own book imprint, Currency, and was prototyping a new magazine. Harriet and I hit it off and I ended up doing some articles for her. She wanted a series about Rasputin-like figures, influencers behind the CEO. But what I found was that companies are not influenced by individuals so much as by ideas that seem the opposite to what the companies were trying to do. I wrote about four of those: scenario planning in Royal Dutch Shell, the quality movement in General Motors, the ideas of Elizabeth Kubler-Ross in Amtrak, and corporate environmentalism at Dow Chemical. They were all really interesting. In the late '80s Dow Chemical was probably one of the most environmentally conscious companies in some ways, and in some ways completely not and I wrote about that dilemma. I basically built my freelance writing career around that series and then began working on other peoples' business books, starting with The Fifth Discipline by Peter Senge [1990, 2006]. That led to The Age of Heretics [2008], my book about the relationship between counterculture and corporate culture. Whole Earth put me on that trajectory, because behind every computer story is a business story and behind every business story is a culture story. That's the basis of the magazine I now edit [Strategy+Business] and most of the business books I wrote between 1985 and 2005.

RH: You're skipping over News That Stayed News. Is that because you want to forget it?

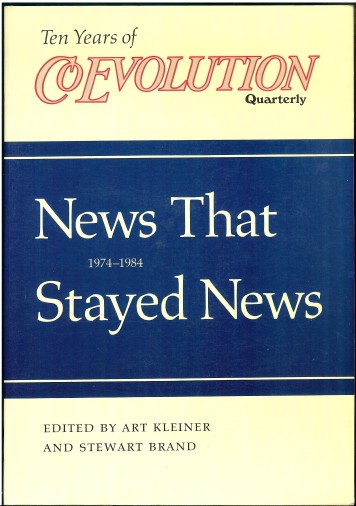

AK: No, I'm very proud of it. As an aficionado of magazines I also love magazine anthologies, and if ever a magazine deserved an anthology it was CoEvolution. Because I was the guy in charge of books at Whole Earth, I got to know a lot of editors and publishers. They all wanted me to feature their books but I was completely incorruptible because I had no power to decide what books got published reviews. But they tried to influence me anyway, by talking to me and giving me books. It was great! One of the most interesting editors I met - and one of the most interested in what we were doing - was Jack Shoemaker at North Point Press. One day I asked him, what would you think about an anthology of CoEvolution Quarterly? Wendell Berry had written: "literature is news that stays news." So in a review of one of Berry's books, Stewart wrote: "his news stays news." I thought, what a great name for an anthology. So we signed a contract with North Point and it gave Stewart an opportunity to revisit articles he had published and rewrite introductions to them. Whole Earth had published a huge amount of material over the years that was worth holding onto, much too much to contain in one book. We published almost 600 pages every year.

RH: No advertizing, so you had lots of space.

AK: We decided we were not going to republish anything that had appeared in any of the Catalogs, and we excluded reviews, so we just published articles and ended up with a book that I think still stands up. But it didn't sell well.

RH: Why?

AK: I don't know. Because there are too many books and too few readers. Because we didn't market it effectively. News That Stayed News might have sold enough to meet expectations, but I don't think there were ever any royalties from it. It certainly was a testament to what I still feel, that CoEvolution Quarterly was a great magazine. Whatever else Stewart has done, he published one of the great magazines between 1975 and whenever he left - 2003 I guess.

RH: You mean when publishing stopped.

AK: When he left as the editor.

RH: Oh, that was earlier. Then there were guest editors, Jay Kinney and you, then Kevin, Howard and Peter Warshall, right?

AK: I was never that independent. I was developing things but Stewart was still pretty much overseeing the magazine the entire time I was there. If that changed, it changed after I left.

RH: News That Stayed News is a beautiful book - I have both the hardcover and the paperback editions - but I've heard from other people that anthologies in general just don't sell, and that's a problem. At the time I thought it was a bigger problem that the book looked so different from the magazine. Readers wanting to refresh their memory of CoEvolution might not find the book attractive, even though it looked good and had CoEv content, just because it didn't look or feel like CoEvolution. It looked like fine literature, not a homemade newsprint kind of thing. I wonder if it didn't sell because of an inappropriate format like the Software Review.

AK: News That Stayed News looked like literature because North Point Press was a literary publisher. We wanted something like what North Point did. But I want to answer a different question.

RH: Sure, go ahead.

AK: If I get to speak at the Whole Earth reunion, one of the things I want to say is what I'm about to say to you. I talked about it with John Markoff but I don't think I've ever talked to Stewart or anyone else at Whole Earth about this. For about a year and a half I've been really conscious of the difference that Whole Earth made in terms of civilization. I've been working on a book [The Wise Advocate: The Inner Voice of Strategic Leadership, to be published by Columbia Business School Press] with a neuroscientist, Jeffrey Schwartz, who has a strong interest in religion. Working with him has made me think a lot about religion and the Enlightenment. To me, Stewart's phrase, "We are as gods and might as well get good at it" is incredibly profound. People who are religious tend to think God sets boundaries for human endeavor. Those who transgress those boundaries are sinners. Those who do it deliberately commit the sin of pride - hubris - for which there is always a penalty. That is the human condition. Pride goes before a fall.

But when you say, "We are as gods and might as well get good at it," you're casually endorsing the sin of pride and saying it's not a sin at all. But neither are you being arrogant. You're saying it's up to us to make our lives better. We may fail, but we're going to keep trying. We're not going to assume that our trying will provoke divine retribution, that we will be shamed for competing with cosmic forces - because we don't believe we are competing with them. We think that despite all the misery of being human, those forces are with us and we're going to keep trying to do better because trying to do better is part of the human condition, too. We're going to accept our inner demons. We're going to accept our animal nature as well as our divine nature. We're going to accept that we can be broken by circumstances. But we're also going to recognize that we can rise above our circumstances - deliberately, with our intellect, our wits, our emotions and our bodies. We're going to assume we can improve all of these, here on Earth, without waiting for an afterlife. And even if we fail, even if we exploit others, we're going to assume we have it within ourselves to improve. All we need, as the Whole Earth Catalog said, are the tools. Of course, this might be wrong. Maybe there is a judgment coming. But while we're waiting and uncertain, why not try to make the most of our existence? We might as well get good at it.

The self-help book industry - the nonfiction make-things/do-things/help-things/solve-things book industry - came to life in part because of the Whole Earth Catalog. And one of the reasons for that, I think, is that once you say, "we might as well get good at it," it's not God's will, it's not fate, it's my will, and if I fail I'm just going to keep trying. Let me take this humanity out for a spin and see what I can do. Once you say that human beings have "original virtue," if you're going to be intellectually honest then the only way out is what Stewart found when he created the Catalog. It was implicit in the counterculture. It has probably been implicit in every counterculture since there was a church, any church. But I think that of all the many things Whole Earth will be remembered for, that phrase - "we are as gods" - will be one of the things most remembered.

RH: Beautiful. Let's end there.

.jpg)