Go to Whole Earth Collection Index

Danica Remy Interview

by Robert Horvitz, 30 May 2018

Go to Whole Earth Collection Index

by Robert Horvitz, 30 May 2018

RH: Danica, near as I can tell, you fell into Whole Earth's orbit through the Global Business Network, is that right?

DR: Not exactly. In 1986 I answered an ad that Stewart ran in the Pacific Sun that basically said "My name is S. Brand, I'm looking for someone who knows computers, wants to work at home, lives in southern Marin, wants to travel and meet interesting people." I had been doing computer consulting for almost ten years and built my first PC with my Mom - we found the parts suppliers in the Whole Earth Catalog. So when I saw his name and saw that the phone number began with 332, which was only for Sausalito, I knew exactly who it was and I ended up writing a fan letter. That led to me running something called the Learning Conferences with Stewart, which was a precursor to the Global Business Network [GBN]. Part of my job was helping corporations get onto something called the Notepad and in our second year we decided to move folks over to The WELL. So the connection was definitely through Stewart but it was before GBN.

RH: So you were involved with The WELL, too?

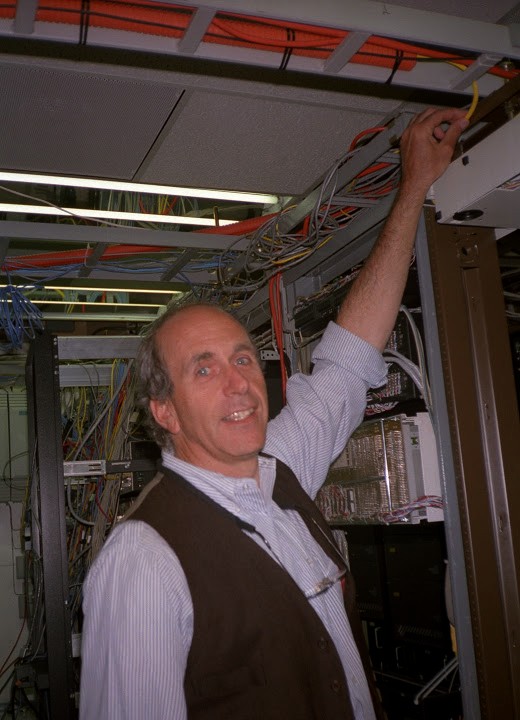

DR: Yes, and a few days ago I pulled out the boxes where Whole Earth's administrative papers are stored. If you give me a few minutes I'll go get them so I can give you exact information. [Pause] Point Foundation and Networking Technologies International [NETI] formed a joint venture in January 1985 to develop The WELL, and The WELL's first day in service was April 1, 1985. Matthew McClure ran The WELL from 1985 to 1986. Then John Coate ran it from 1986 to 1991 and Cliff Figallo came in eight months after John. Those were the first hires. The Learning Conferences had me teaching people how to use The WELL and I introduced it to Bruce Katz. Bruce fell in love with The WELL and decided to buy NETI's share in 1990. He bought the rest of the shares in 1994. I left GBN to run The WELL in 1994 after Bruce finished his acquisition. After the acquisition, Bruce Katz made significant investments into the WELL and the infrastructure to enable so much in the following years. The WELL was hugely influential and Bruce single handily kept it going and growing when Point Foundation and Whole Earth could not. I have a vivid memory of showing Bruce The WELL on his little Macintosh in 1987 at his house in San Francisco. He had taken his Mac out on the beach and sand got inside it, so we had to vacuum the sand out of the opening in the back. When he got on The WELL, his first question was, "You mean, I could talk to aqua-farmers all around the world who are raising salmon?" And I said, "I suppose so, if there's a conference about that."

RH: I don't recall any aqua-farming conference on The WELL.

DR: I guess not, but there might have been something on Usenet. There were not alot of people yet on the Internet. Going through this box of papers, I found that there was a matching challenge in 1989 to raise money from The WELL's user base.

RH: They probably had to upgrade the hardware.

DR: Right, they had to invest in the platform, and second - this is hearsay, as I was still working for GBN and didn't know much about the WELL's problems - they had to overcome some dysfunction between the Whole Earth staff and The WELL staff. The person who was hired to run The WELL sometime in 1990, Maurice Weitman, did not get along with a person I'm going to refer to as He Who Shall Not Be Named, who was running Point, the entity that ran both Whole Earth and The Well and which still exists today. So there was an ongoing set of conflicts and I think that ultimately led to the full sale of The WELL to Bruce Katz.

RH: Why do you refer to that person as He Who Shall Not Be Named?

DR: Whole Earth and Point have a separation agreement with him which limits what I can say. I don't know how much you've talked to people about the ending years of Whole Earth but Stewart, myself and others had created this thing called GBN in 1989 and in 1990 I had a baby. In 1991 - this is my assessment - Stewart wanted out of everything having to do with Whole Earth and The WELL and was trying to put in place a new team. He reached out to me and said would you come run Whole Earth and The WELL? I was a brand new single mother and I said I love what we're doing at GBN, I don't know that I could run a publishing operation and oh, by the way, I'm frightfully dyslexic and scared to put anything on paper or online because my spelling and grammar and proofing are so atrocious. So I declined. And after that, Stewart and the board hired someone else.

RH: So that agreement is why you can't reveal his name.

DR: He arrived into an organization with revenue and expense problems, a gangly, distributed and perhaps entrenched staff, etc., and to make a long story short, they had to suspend publication in 1995. But then in 1996 a group of folks tried to bring it back, led largely by Ty Cashman and Peter Warshall (there may have been others I didn't know about). They had raised tranches of money from a group of ongoing supporters, and unbeknownst to me, they also borrowed money, which was never booked into the accounting. That was in 1996. The Internet was expanding and to pursue this revolution in communication, I left GBN and accepted Bruce Katz's offer to run The WELL. The relaunch group also wanted me to help Point think about business strategy and what an Internet strategy might be. So that's how I got on the board of the Point Foundation. I've been on the board since then and was ultimately responsible, along with the board, for shutting down Whole Earth. And in partnership with the board, I was responsible for the licensing of Whole Earth's intellectual property at the end.

RH: So things hit bottom in the mid-90s and started to come back, sort of, when Peter raised money to resume publication with a new staff? Then what happened.

DR: Well a couple of things. Postage costs went up. Printing costs started to go up, too, and the print publication business was shrinking. And we didn't have an Internet strategy because the Point Foundation no longer owned The WELL. Plus in 1996 no one knew what the revenue model would look like for online publication. I said to Peter and the board if we raise money for an Internet strategy, I don't know what it would be - it's just a sinkhole and a big gamble, as far as I could tell. And I wasn't willing to advocate for this kind of risk without clarity on how we were going to fund it. Howard and Kevin had already been peeled off for Wired sometime in 1993. This was when He Who Shall Not Be Named was selling The WELL and Stewart was totally disengaged, as I think you probably heard. When Stewart's done, he's done, and he just walks away. That came out in a couple of your other interviews. So by 1993, the remaining staff was running the remnants of the publication. They had already committed to a book deal that happened before He Who Shall Not Be Named arrived.

RH: That was the Millenium Catalog?

DR: Yeah. Hold on, I can actually get out that contract. [Long pause] It must be in another box.

RH: That's okay.

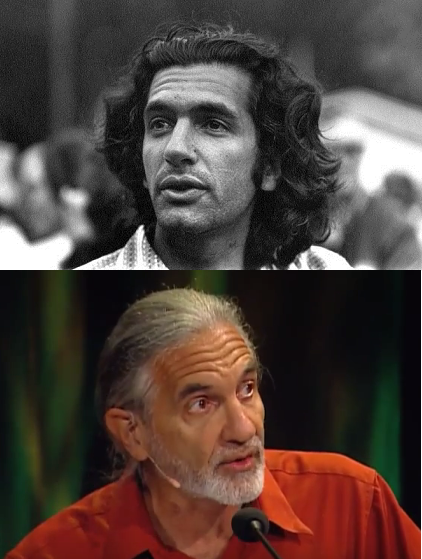

DR: But it's relevant to the crisis at Whole Earth. Through management and operation decisions, He Who Shall Not Be Named spent most of the money from the sale of The WELL and the advance on the Millenium Catalog. The board members had been through alot and were tired of the strife between the Whole Earth staff and The WELL staff. Stewart was tired. We were in a process of building GBN and he was enjoying the ideas we were exploring in the business network. Peter Warshall did an amazing thing reviving the magazine. He had been involved in editing many sections of the Catalogs and described himself as a "maniacal naturalist." He was an incredible intellectual, whether it was poetry or philosophy or the environment, but he didn't easily go into the world of technology - a key theme of the Whole Earth publications - or business. He was interested in those things but he didn't want to include them in the magazine. He had a really strong point of view but he was a Luddite, as he always told everyone. The world was changing around Whole Earth yet he continued to focus on environmental stewardship. And so while in the early years, and in the years before the collapse, there was a broad spectrum of content, Peter stuck with J. Baldwin, Cool Tools, the environment and poetry. The other subjects that the Catalogs covered - sociology, technology, self-organizing systems - those parts of the "whole" of "Whole Earth" got de-prioritized because they weren't in Peter's comfort zone. And so what was already a niche, from a readership perspective, got even more nichey.

RH: Did this lead to conflict between the editorial board and Point? Because it strikes me that it would have been up to Point to say listen, what you're doing is perfecting a shrinking niche and that's not a good survival strategy.

DR: I don't have any knowledge of such a conflict. When I joined Point there was an editorial board but it was really run by Peter, so it reflected Peter's point of view. Whole Earth's managing editor, Mike Stone, provided some balance. Mike's area of interest was human health, so he made sure we had some of that in each issue. But we didn't really have a functioning editorial board and I don't think historically that the editorial board set policy. It existed to support the person running it, which was Stewart in the early years.

RH: Well, it must have been Point that decided when to say look we're out of money and we have to stop publishing, right?

DR: What happened was that Peter wanted to go back to Tucson. Peter had largely held the publication and staff together as we recovered from the collapse in the mid-90s. But the staff were all located in Marin County and he didn't want to be the business manager. So we hired a business manager who lasted less than 12 months as I remember. The person we hired to be business manager really wanted to be the editor and that caused internal conflict. The board knew that we were already struggling from issue to issue, and even skipped an issue or two. One remarkable board member helped bail us out more than once after the relaunch, but they were done. The new business manager and the development person told the board there was money in the pipeline when there was no money in the pipeline. When it came to print what became our final issue, we were in debt from the prior issue and didn't have any real hope of getting enough support to keep going. The final issue was never printed but it can be found online.

RH: This was in 2003?

DR: Yes. We had to let everybody go because there was no money left to pay the staff. And no money to pay the creditors either. So the Point board made the decision to shutter the operation.

RH: Ooo, painful!

DR: There was nothing left. There was no staff, no community to support this newly reconstituted rendition of Whole Earth. And so all of the closing, all of the triage, all the going through 40 years of publications, organizational material, books that had been given, research materials, staff files, subscriber tapes that were still in those huge cans - all that largely fell to me with limited help from the other board members. And I had a fulltime job. I was running a really big operation at the Tides Foundation and people would say, why are you doing this, going through every single box and throwing things into dumpsters? And I said because even though the founders and the early people that were part of Whole Earth no longer cared and had gone on to other things, it's a cultural icon and I know that the papers are valuable from an historical perspective. I felt a very deep sense of obligation to maintain what vestiges I could of what was Whole Earth. My mother kept her Whole Earth Catalog out on the table! I knew how important it was to her, so therefore I knew it had to be important to other people, too, and I had to take care of it.

RH: How did Samuel B. Davis come into the picture?

DR: After we closed the doors, I went to everybody I thought could help and said look, here's the situation. We owe over a hundred thousand dollars to the distributors, to the printers, to the staff, for rent and for storage lockers - and we have this great asset - forty years of what was published in the pages of Whole Earth. Somebody has to want this. I went to Stewart and he just wasn't interested. He had long ago moved on from Whole Earth. He said go talk to Brewster Kahle. So I went to talk to Brewster, who at that point was working on his bookmobile. And Brewster said, well you could just scan everything and put it free on the web. And I said I could, but I have no volunteers, no scanner and no money. So he said well I can't help you. And so I went to Kevin and to Howard and the problem was just daunting to the original participants. And so I put all the creditors on notice that they were going to be in the queue as soon as I figured out what's left with the organization, asset-wise. And I sent notices to all the subscribers. There was no staff to do any of this but I felt an obligation to the institution. So I took everything from Whole Earth and boxed it up as best I could and thanks to my colleagues at Tides, I stored 1200 or 1500 square feet of historical stuff in Tides' basement for free. Tides of course was born in the 1970s so they understood the value of Whole Earth. And I talked Tides into creating a Whole Earth Library in the Thoreau Center in the Presidio. We took alot of the books and reference materials and put them into a library that was open to the public. Unfortunately, it's now closed. Essentially, I put everything on ice. This is a long story to get you to Sam Davis.

So we had an asset, and Kevin and Stewart and Howard would talk to some - for lack of a better word - "interested" entrepeneurs that had some great ideas about what to do with Whole Earth and they would point them to me. And I would say to them, what's your idea about leveraging the content? What would you do with the brand? And they had all these ideas, and I would say, well how are you going to make all this happen? And they would say you're going to help me raise the money. And I had to explain that the Point board was exhausted from keeping Whole Earth going for as long as they did. They aren't able to help you raise money. This is a business opportunity. So I had about ten of those noisy interactions, where they wanted the content, the brand, and my help but weren't willing or able to put their own money into it. They wanted alot of access to people and my time. I got to the point that I had a canned email response that went something like this: "Hi, you're right that Whole Earth is a great asset and I'm happy to talk to you about it, but you'll need to confirm that you have a quarter of a million dollars and are prepared to put that on the table now." That made the noisy people go away! And then, out of nowhere, I got an email from someone named Sam Davis. I sent him my standard email letter and a day and a half later, he replied: yeah, I have that, let's talk.

RH: So then you had a phonecall with him?

DR: Yeah, and after alot of chatting he realised that we were in a distressed asset situation and we had a board with people who still thought we should just keep the asset on the shelf. My response to that was that we owed over a hundred thousand dollars, over thirty thousand of it to loyal staff members who contributed to this project over decades. We're going to keep it on the shelf and stiff the employees, staff and writers? That was part of what I call the closing tensions. I knew what my fiduciary responsibility was and I didn't feel good about leaving people unpaid. I didn't feel as bad about the printers and distributors. We made the staff and writers whole in the end and then paid vendors about 20 or 25 cents on the dollar, which they were happy to get instead of taking us to bankrupcy court where they might end up with nothing. So we licensed the intellectual property to Sam for 50 years. I went to Columbus, Ohio, and met with him and his web developer and designer and spent four days brainstorming with him about ideas and going through the WholeEarth.com website before it was rolled out. I felt we were starting a good partnership so I'm sorry that Sam became nonresponsive. The unfortunate thing was that he wanted a trigger which said if his entity, New Whole Earth LLC, ever started to leverage the content in any way, then he would pay the second half of the money. But someone on the board wanted the trigger to be New Whole Earth hiring someone with the title of "executive director". That means the second payment probably won't happen because they can just not use that title.

In the end I felt pretty good that the staff and creditors got paid, and Sam doesn't own the rights to individual articles [just the rights to entire issues of the magazines and catalogs]. It's messy for people who might have been on staff, but that's the story. It was not an easy negotiation. Sam is a complicated guy. He grew up in the late 60s as a Republican Christian in the midwest when he found a copy of the Whole Earth Catalog and for the first time in his life realised that his church and school were not the only places he could find information useful for thinking about his future. The Catalog was seminal to him and he reached out to us because he wanted his children to see that he was involved in something beyond business. In his mind acquiring Whole Earth was part of his legacy. Essentially he saw something really cool, decided to buy it, and has done very little with it beyond making scans available online.

RH: He hasn't done much with it because he didn't get the response he wanted?

DR: Perhaps. If you reach out to him, I hope you can convey that I'm deeply appreciative of his making everything that Whole Earth published available to the public through the website. That's a huge gift. I don't know what it cost him to scan every book, every article, every issue of the magazines, etc. I'm guessing it cost like 25 or 30 thousand dollars, maybe more, who knows? What I want to communicate is that even though the original Whole Earth community did not see the value and rally around the digitisation of the work published during the prior 40 years, Sam Davis understood how important it was to put those seminal publications online and we should be grateful for that. Even though the website's online PDF reader hasn't worked for years, all the scans can still be downloaded.

RH: So what are you doing now, Danica?

DR: It's so amazing. It's like the ultimate environmental project, right? When I first joined B612, Stewart interviewed one of the founders, Ed Lu, a 3-time Shuttle astronaut, for the Long Now series. And in the opening of the interview Stewart says that if B612 wasn't doing this, this is exactly what the Long Now Foundation would be doing, because this is such an important long-term and short-term project. It's incredibly exciting. I love being part of it. I was the Chief Operating Officer of the B612 Foundation for four and a half years then President for the last year and a half. We're dedicated to protecting the planet from asteroid impacts. Most of our expenditures now are for developing a software platform to analyse data that will be coming in a few years from a telescope called LSST [the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope] and other sources. That will enable us to track about 50 to 100 thousand asteroids passing near Earth. We need a software platform with analysis and forecasting capabilities to determine if any of them are going to hit the Earth, and what it would take to deflect one that is. It's driving alot of new insights about probability and statistics, ranges of uncertainty and calculating orbits with imperfect data. To put this in perspective, right now NASA has in its database of all known near-earth asteroids 18,000 of them. But there are believed to be about 3 to 5 million as big or bigger than the one that blew up over Chelyabinsk 5 years ago, sending 1500 people to the hospital, blowing out 100,000 windows, and with a shockwave felt half way across eastern Europe. So there are alot more asteroids that we need to find and map.

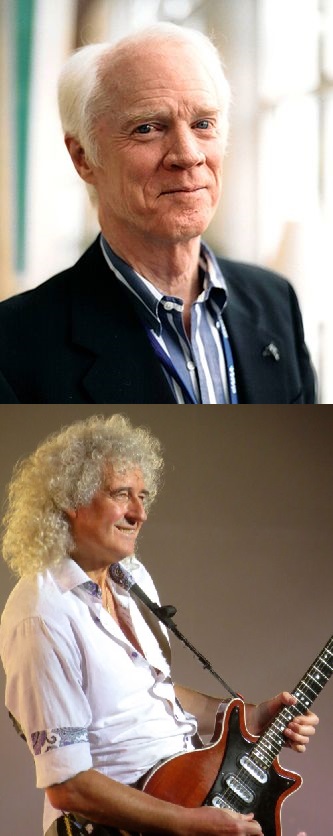

When I first joined this organisation, which has been around for 15-16 years now, I realised that part of the problem is that few people appreciate the risks posed by near-earth asteroids. Even though you can get the press to cover astronauts expressing their concern, the rest of the world was not taking the issue seriously enough. So we enlisted Rusty Schweickart, one of the Apollo 9 astronauts, who was a co-founder of B612, a young filmmaker from London [Grigorij Richters], and Brian May, the lead guitarist from Queen who became an astrophysicist. We proposed that there should be a global day of education and awareness about asteroids. So that's how Asteroid Day emerged. We enlisted 150 notable people - including Stewart Brand! - who share our desire (a) to know where the asteroids are, (b) to invest in technologies that help us find or deflect the asteroids, and (c) to educate the world about asteroids. Asteroids are important for understanding the origins of life and how we might move farther into space. Water is common in asteroids and it can be split into oxygen and hydrogen to be burned as fuel for long distance space travel. And finally, sometimes asteroids hit the Earth so we need early warning. That's what prompted us to create Asteroid Day.

RH: Which is on June 30th?

DR: Asteroid Day is on June 30th. We use the Earth Day model: most of the events on Asteroid Day are locally organised. We just publicise them globally. Last year we had 1300 events in 200 countries, attended by about about a half million people. And that was just our 3rd year of operation. This year we're hoping for 2000 events.

There are times when I look back on that ad Stewart wrote more than 30 years ago that said "I'm looking for someone who knows computers, wants to travel and meet interesting people." Answering that ad led me into such an incredible set of life experiences. Without the serendipity of joining the extended community around Whole Earth I would not be here today working to protect our home planet.